Science Is Basically, Like, a Miracle

In continuing to read Against Method, I’ve now gotten through chapters 5 and 6, which discuss observations and interpretations. Chapter 5 covers the fact that basically all scientific endeavors frequently include ad hoc reasoning that isn’t striclty based in observation or fact. In the very early literature, such ad hoc reasoning was made explicit in the text, which causes modern audiences to look down at those scientists (Bacon, Galileo, Newton, Descartes, etc.) as less than rigorous specifically due to their admissions of such ad hoc reasoning.

However, Feyerabend notes, it is not that the ad hoc reasoning has disappeared from the sciences (see the Turing quote in the Against Method note for example); it is that the ad hoc reasoning has ossified into the greater cosmology of the scientific project and is thus obscured from view almost all of the time. Feyerabend provides a litany of examples in Chapter 5 of scientists engaging in ad hoc reasoning, ranging from Bacon to Einstein to Bohr to von Neumann (bear in mind much of the text was written in the ’60s and ’70s so that last is a fairly contemporary reference). The point isn’t so much to say “scientists do this all the time, therefore science is bad,” but rather to expose that there is an immense vocabulary of observational interpretation implied by basically all scientific work, and in this vocabulary lies those ossified ad hoc reasonings that form the foundation of modern scientific thought.

Lest you think I am making a mistake by stating “observational interpretation,” and not “observation” then “interpretation,” what I mean is “the process by which an observation occurs” in a scientific context. Feyerabend argues, I think fairly convincingly, that observation and interpretation are fundamentally, inextricably linked. To wit, if Newton watches an apple fall from a tree, there’s a huge amount of complex processes that occur to allow him to make the observation that the apple is falling, all of which involve interpretation at every step. The light from the apple, the tree, and the ground have to hit his eye, then his eye has to convert the photons into neural signals, which then have to be processed by his brain to convey meaning to what is occurring. Language is already introduced here, as his brain understands that there is an “apple”, it is “falling,” it originated in a “tree”, and it is separating “from” it. Let alone all of the other machinery required to rigorously document the event, like a clock, paper and pen, etc. Even in this relatively simple process, there is so much room for subjective experience to enter into the process of recording observations of experiences, because there is so much room for subjectivity in experience in the first place!

As an example from my own work, we frequently say things like “[…] select ballots to inspect. Record votes on all inspected ballots.”12 There is a mountain of procedure specified in those ten words, and not just because I cut out the text about how to choose which ballots to observe. Auditors must select the ballots according to our procedure, retrieve them from storage, arrange them in such a way that the votes on the ballots may be observed, go through the ballots and observe and record the votes on each one, tally up the results of the recorded audit data, do the math (or really enter the data into a computer that does the math), put the ballots back, maintain chain of custody documentation the whole time, and so on.

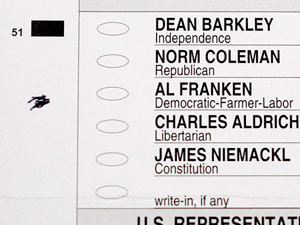

Even one of these steps conveys a continent of observational prescription. For example, “observe and record the votes on each one” is an astonishingly complex task. Presumably, “observe” means “look at the ballot and determine what vote is recorded on it,” but even that is ludicrously complex. It implies that such a determination will be made in a way that is consistent across both time (i.e. the same person looking at the same ballot will make the same determination) and auditors (two different auditors looking at the same ballot will make the same determination). This is an impossibility a non-trivial amount of the time! For example, how would this ballot be adjudicated?3

This is to say nothing of the actual act of observing a ballot in the first place, which involves the complex workings of the human eye and brain, and light, as previously discuss with Newton and the apple, properties of ink and paper, and so much more. In making that statement, we are assuming that optics function in a way that has been well documented (and experienced by humans for functionally all of time). We are assuming the auditor’s brains and eyes function like those of our own (for example, if red ink is not considered a valid mark,4 a voter marks a ballot in green, and the auditor has deuteranopia, our statement doesn’t really account for dealing with this situation).

The point here is that when scientists make statements like “observe the ballot” there may be a lot of ad hoc reasoning buried deep within them. It is truly miraculous that science can make meaningful predictions about anything at all! It is no wonder that skeptics can run roughshod over the modern scientific landscape, making claims that depend on nuanced dialog between scientific sources to suss out whether such claims are really “true” or not, let alone whether or not such claims will lead us to create better lives for people.

I was interested in Feyerabend’s ideas before these chapters, but now I’m hooked. I expect to be disappointed.

-

Ottoboni, Kellie, Matthew Bernhard, J. Alex Halderman, Ronald L. Rivest, and Philip B. Stark. “Bernoulli ballot polling: a manifest improvement for risk-limiting audits.” In International Conference on Financial Cryptography and Data Security, pp. 226-241. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2019. ↩

-

That’s right, this is one of those blogs. With footnotes. And references. ↩

-

Ballot adjudication is a wildly nuanced and complex topic on its own, and it’s different in every jurisdiction. This is by no means intended to be a comprehensive or even really accurate discussion of it. ↩

-

This used to be fairly common, as older optical scanners used red lights to detect marks on ballots. If you’ve ever wondered why teachers could mark scantrons in red pens without impacting the results, now you know. ↩

Notes mentioning this note

There are no notes linking to this note.